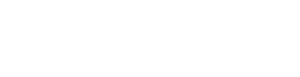

The great Albanian nobleman Gjergj Arianiti, father of Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg’s wife Donika, was a hero and powerful warrior against the Ottomans in his own right. He was the eldest of three sons (the others being Muzakë and Vladan) of Komnen Arianiti Spata, who ruled an area outside Durrës. (Its unclear who Gjergj’s mother was but according to socialist realism historian Dhimitër Shuteriqi she was a daughter of Nikollë Zaharia.)

Read more...

Born in 1383, young Gjergj witness the beginning of the Ottoman invasion of Europe; the victory of Sultan Murad I in 1385 at the Battle of Savra—near Lushnjë, it was not far from his ancestral home—as an ally of Prince Karl Thopia of Krujë against Balša II of Lower Zeta (the area around Lake Shkodër) marked the start of Turkish hegemony in Albania as the Albanian chieftains ruined each other. When Gjergj was 6 Murad marched into Kosova and defeated a Serbian-led Christian army under Prince Lazar. (At the Battle of Kosova the Albanian chieftain Teodor II Muzaka—whose descendant Maria would marry Gjergj—was killed, with the Albanians being led home by Skanderbeg’s father Gjon Kastrioti.) Gjergj’s father, much like Gjon Kastrioti with Skanderbeg, was forced by Murad to surrender his son as a hostage to be kept at the Sultan’s Court in Edirne to keep the Albanians from revolting. Thus Gjergj Arianiti was a captive of the Turks from 1423-27 when he finally returned home, burning with revenge.

When Gjergj Arianiti (or his full name: Gjergj Arianiti Thopia Komneni according to the historian-statesman Bishop Fan Noli) returned home at the age of 44, his people and Albania in general has been greatly reduced by the Ottoman usurpers who had come to dominate the entire Balkans. 28 year-old Sultan Murad II, having secured his reign by defeating & killing his brothers Düzmece Mustafa and Küçük Mustafa, now turned the screws on the Albanian nobility. He further reduced their power and influence in local affairs in favor of Ottoman officials drawn from their own ranks by the devşirme blood tax that forced subjugated families to surrender sons to be converted to Islam and trained to serve the Sultanate.

Skanderbeg at this time was in fact a young officer serving Murad, who was only a few years older than him, having been taken from Gjon Kastrioti via the devşirme. In early 1432 Andrea Thopia, Lord of Scuria (the region between modern Durrës and Tiranë) started a small peasant rebellion which quickly spread. Arianiti joined the revolt, as did old Nikollë Dukagjini from the North; soon all of Albania was aflame. Gjon Kastrioti joined the rebellion as well, summoning his son Gjergj, but Skanderbeg remained with the Sultan, who did not send him to fight against Arianiti, but kept him busy fighting in the east.

Sultan Murad himself marched from Edirne in 1432 with an army intent on breaking the Albanians; he made a strong base in Macedonia and sent the Sanjakbey (Governor) of Albania Ali Bey Evrenosoğlu at the head of 10000 men against Arianiti. Marching up the Via Egnatia along the Shkumbin River to penetrate central Albania, the Turks were ambushed by Arianiti at Bërzeshtës and defeated. A second force under Ali was caught and destroyed in 1433 in a tight valley near Kuç, and Arianiti was celebrated throughout Christian Europe, hailed as “The Protector of Freedom.” In 1434 he won a 3rd great battle against Ishak Bey (who had crushed Gjon Kastrioti’s forces a few years earlier)—Ishak barely escaped capture, while most of his Turks were taken prisoner—and Arianiti was restored in Vlorë and his hereditary castle at Kaninë.

Venice, Ragusa, the Holy Roman Emperor Sigsimund, King Alfonso of Naples, and Pope Eugenius IV all promised aid for the Albanian cause, but delivered little. Thus the inexhaustible resources of the Ottoman Empire were marshaled yet again, and armies under Ali Bey and Turahan Bey were unleashed in 1435-6. Arianiti eventually was worn down, retreating into the mountains of Skrapari.

Murad made peace with the indomitable Albanian, granting him control of his lands from the Shkumbin to the Vjosë, which the Ottomans could not take from him anyway. Gjergj Arianiti, now 53, accepted this peace and bided his time for when he could strike yet again and free his people forever. He saw his opportunity to rise up once more against the Ottoman Empire in August 1443 when news came that Kula Şahin Pasha, Governor of Rumelia (all the Sultan’s lands in Europe) had been badly beaten by the Hungarian knight John Hunyadi and Vlad the Dragon in Wallachia. With support from Pope Eugenius IV, Arianiti set out at the head of his small army into Macedonia.

Meanwhile, in November Hunyadi defeated the new Governor of Rumelia Kasım Pasha

(who himself was Albanian), along with the old adversaries Turahan Bey and Ishak Bey, at the Battle of Niš in Serbia. On the eve of battle Skanderbeg, a cavalry commander in the Ottoman Army, rode away at the head of 300 Albanians to head back to Krujë and join the growing rebellion. In his company was his nephew Hamza Kastrioti and his trusted lieutenant Moises Golemi, who was a nephew of Gjergj Arianiti.

In March 1444 Arianiti answered the summons of Skanderbeg to meet in the Venetian stronghold of Alesso (Lezhë) with the other heads of the noble families to form a new union against the Sultan. Along with Andrea Thopia and his nephew Tanush, Teodor Muzaka, Lekë Zaharia, Pal and Nikollë Dukagjini, Pjëter Spani, Lekë Dushmani, Gjergj Strez, Gjon and Gojko Balsha, and Stefanica Crnojević of Upper Zeta, Gjergj Arianiti—the primary leader of Albanian resistance in the decade leading up to this moment—and Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg declared a pact known in history as the League of Lezhë. Seeing that the younger man Skanderbeg was an exceptionally talented leader of men, Gjergj Arianiti joined the others in declaring an oath of besa to each other & named Skanderbeg "Chief of the League of the Albanian people" and Dominus Albaniae, Lord of Albania. Arianiti continued to lead his own men on the field of battle, but in every instance that Skanderbeg appeared in battle, he was the supreme commander, and victory followed Skanderbeg wherever he went.

After six years of near-constant war, cracks in the League were beginning to show. Gjergj Arianiti and Skanderbeg tried to make a formal alliance with Venice, but sensing imminent collapse, Venetian Senate demurred. At the head of 3000 warriors Arianiti beat a Venetian force along the Drin River, as Venice perceived the Albanians to be weakened and thus sought to expand along the coast and seize Vlorë from Arianiti. Skanderbeg delivered the final blow against a larger Venetian army under Daniele Iurichi, governor of Scutari (Shkodër) and Venice paid the Albanians 1400 ducats to secure peace.

Now Murad struck. First Svetigrad surrendered, then Berat in early 1450, and Arianiti, now 67, laid down his arms. But when Murad and his teenage son Mehmed besieged Krujë, Arianiti again took to the field and helped Skanderbeg defeat the Ottomans. Arianiti and 4000 men joined Skanderbeg in an attempt to retake Svetigrad fortress near Lake Ohrid, where the old nobleman displayed great bravery on the field of battle. But sadly his younger brother was killed during the failed siege.

Yet because of the great resolve of the Albanians, Skanderbeg and King Alfonso of Naples signed the Treaty of Gaeta in March 1451. The Neapolitans signed similar independent treaties with Gjergj Arianiti and the other nobles, guaranteeing financial support and arms—especially artillery—in return for swearing an oath of fidelity to the Neapolitan crown. A month later Skanderbeg married Donika—the eldest of Gjergj’s 10 daughters—which cemented the alliance of the Arianiti and Kastrioti families.

In 1455, Teodor III Muzaka—relative of Gjergj Arianiti’s wife Maria Muzaka—lay ill in his fortress of Berat. He sent for Skanderbeg to come take possession of the castle, but before his lieutenant Pal Kuka could arrive, an Ottoman force snuck over the walls, murdered the Albanian garrison of 500 men, and hung the old nobleman. Now Skanderbeg himself arrived on the scene, joined by 72-year-old Gjergj Arianiti and his horsemen as well as a 1000 man Neapolitan contingent skilled in artillery and siege warfare. But when it looked as if the Ottomans locked within the Castle of Berat were about to surrender Skanderbeg departed to check on the enemy’s approach from Vlorë, leaving Karl Muzaka Thopia in command. It was then that old Ishak Bey Evrenoz appeared with 20000 Ottomans to smite the Albanians in their camp along the Osumi River. 800 of the Neapolitans were destroyed, Thopia was killed, his uncle Gjergj Arianiti’s men were beaten and scattered, and only brave Vrana Conti withstood the onslaught until Skanderbeg appeared. The Dragon of Albania rode headlong into the fray, personally driving off the Ottomans “with sword & mace.” But the siege was over and Berat remained in the hands of the Sultan. Gjergj Arianiti’s power in the south was broken for good.

Good news came in 1456, when it was reported that Donika had given birth to Gjergj Arianiti’s grandson Gjon II Kastrioti. Her full name was Andronika Arianiti-Komnenos Muzaka at birth. The Arianiti family, possibly of Illyrian ancestors, had roots in Byzantine Dyrrachium from as early as the 9th Century, although ancient history is difficult to unravel, with a later addition of relations with the Komnenos family of Byzantine royalty. Her mother Maria Muzaka was of that noble family from the Myzeqe plain outside Berat and Apollonia, loyal Byzantine subjects who were raised to the title of Despot of Albania by the Capetian King Charles of Anjou when he established his rule in the 13th Century. Donika had been born in 1428 at the Castle of Kaninë outside Vlorë, living there until her marriage to Gjergj Kastrioti on 21 Prill 1451 at Ardenica Monastery outside Lushnjë.

As the year 1460 began, old Gjergj Arianiti—all of 77 years—took the saddle once more against the Ottomans. For his lifelong enemy Sultan Murad had died and his son Mehmed, called the Conqueror for having taken Constantinople with his mighty artillery six years earlier, was invading Albania yet again. Up the valley of Farka came the Ottoman horde, pushing all opposition out of their way till they reached Shushicë. Here Arianiti’s last warriors made their stand, and his castle Sopoti—which with Kaninë had served these many years as his twin capitals—withstood all assaults. The Ottomans withdrew as if beaten, but returned at night to attempt a surprise attack when the main Albanian force under Arianiti moved off to Galigat, thinking they had been victorious. The small garrison remaining at Sopoti held firm till the end, but through the twin weapons of bribery and treachery—the favorite means of the Turks—the castle fell and all inside were put to the sword. Shortly thereafter, Gjergj Araniti died, and the hopes of his family were carried by the child Gjon II Kastrioti & his father, Lord Skanderbeg, Dragon of Albania.

Donika accompanied Gjon II him when he escaped to Italy after Skanderbeg died in 1468. Donika would never return to her beloved Albania, living instead on the estate in Puglia awarded to her husband by a grateful King Ferdinand of Naples for services rendered during the Neapolitan struggle against Prince Orsini of Taranto and his Angevin allies. When the Italian Wars broke out in 1494 between France and Naples, Donika fled Italy with her grandson Alonso Kastrioti for Valencia in what is now Spain, where her good friend Queen Giovanna of Aragon (King Ferdinand of Naples’ wife) had been born. It was here that Donika died in 1506 and was buried at the Royal Monastery of the Holy Trinity, with Alonso later buried at her side.

-------------------------------------------

This article was written by Mike Joseph known on instagram as @an_american_in_albania whose profile is dedicated to the Albanian history and culture and where you'll find more stories about Albanian important historical characters.